Mr. Anthony Parker, Commissioner of Plant Breeders’ Rights within the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is no stranger to UPOV Affairs. With familial roots in farming and decades of experience in public service, Anthony has represented Canada in numerous international fora on intellectual property and agriculture, contributing to the global dialogue on plant variety protection.

From the global negotiating tables to conducting variety examinations in the cherry orchards of British Columbia, Anthony brings a uniquely grounded perspective to a field that sits at the crossroads of science, policy, and food security -an interconnected landscape he understands perhaps better than most.

In addition to his national role, he currently serves as President of the UPOV Council, the platform where UPOV members take key decisions on the functioning of the organization, shape strategic priorities, and guide the development and implementation of the UPOV Convention through the review of committee work and the adoption of rules, guidance and policies.

In this conversation, Anthony reflects on his professional journey, the impact of plant variety protection (PVP) on farmers and local communities and why fostering innovation in plant breeding matters now more than ever.

You have represented Canada in various international fora related to intellectual property and agriculture, including UPOV. Could you share some insights from these experiences and how they have shaped your perspective on international cooperation in the plant variety protection space?

Mr. Parker: Representing Canada in international fora such as UPOV has deepened my appreciation for the importance of global cooperation. Harmonized systems reduce barriers to innovation and trade, while shared values around fairness and access help build trust. These experiences have reinforced the need for inclusive dialogue and evidence-based policymaking to ensure that PVP systems serve all stakeholders, ranging from smallholder farmers all they way to international breeding companies.

What led or inspired you to pursue a career in this field?

Mr. Parker: I didn’t follow a straight path into this career; it was more of a winding journey that revealed itself over time. I grew up on a farm, surrounded by plants and a rural life, but I didn’t have a clear vision of where that would lead. It wasn’t until I took a summer student job at the Department of Agriculture that I discovered the world of public service and plant policy. That experience planted the seed -literally and figuratively - for a career that would eventually bring me to Canada’s Plant Breeders’ Rights Office.

Mr. Parker and his team conducting variety examination trials throughout the country

Could you give some examples of the impact of plant variety protection and how it benefits local communities?

Mr. Parker: In Canada, PVP has had very tangible impacts. It has enabled the development and commercialization of varieties tailored to local climates and growing conditions, from drought-tolerant wheat in the Prairies to disease-resistant fruit trees in British Columbia. These innovations help farmers improve yields, reduce input costs, and adapt to changing environmental conditions. PVP also supports seed companies and public breeding institutions, fostering a more diverse and resilient agricultural ecosystem.

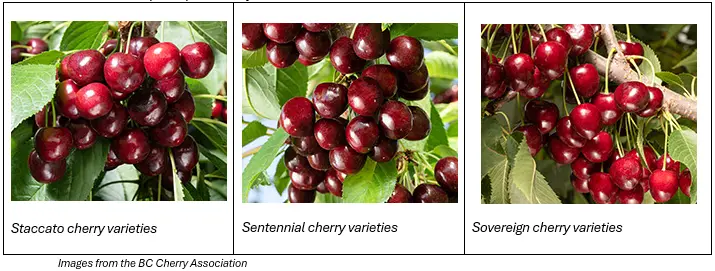

A compelling example is the success of protected cherry varieties developed in British Columbia: Staccato, Sentennial, and Sovereign. These late-season cherries have extended the harvest window, allowing growers (many of them small and medium-sized orchardists), to reach premium export markets and improve profitability.

Canadian cherry growers benefit from government policy - YouTube

The varieties were developed by the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada breeding program and licensed into the marketplace by a grower owned company, Summerland Varieties Corp. Through Canada’s PVP system, they were protected and licensed to nurseries and growers, ensuring quality and controlled propagation.

Growers adopted them based on performance trials, market demand, and traits like firmness, sweetness, and shelf life. Collaboration was central: breeders, researchers, growers, and marketers worked closely together, with producer feedback shaping breeding decisions.

One key challenge is balancing protection with access. In this case, Canada used a strategic licensing approach that gave domestic growers priority access before international rollout. That strengthened national competitiveness while still contributing to global food systems. It shows how PVP can be both an economic and policy tool when thoughtfully designed.

Speaking of economics, what trends or outcomes have you observed since Canada adopted a modern PVP system?

Mr. Parker: Since Canada joined UPOV 1991, we’ve seen a steady increase in the number of protected varieties and a rise in private sector investment in plant breeding. This has led to more competitive seed markets, greater variety choice for farmers, and improved agricultural practices. PVP has also facilitated international trade by aligning Canada’s system with global standards, making it easier for Canadian-bred varieties to be exported and adopted abroad.

According to an IP Canada report, Canada recorded an increase in applications for the protection of varieties following amendments in 2015 to the Canadian Plant Breeders’ Rights Act that brought it into conformity with the 1991 Act of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV 1991).

Mr. Parker: The economic benefits of PVP are multifaceted: increased sales of high-performing varieties, improved yields and higher quality mean more bountiful harvests, more resilient and resistant varieties mean more efficient farming practices, all of which supports greater competitiveness in global markets. Farmers gain access to a broader range of varieties, while breeders are fairly rewarded for their innovation, creating a continuous cycle of investment and improvement.

What about the environmental impact of PVP in relation to climatic effects on agriculture and food security?

Mr. Parker: PVP plays a critical role in addressing climate change and food security. By incentivizing the development of resilient, high-performing varieties, it helps farmers adapt to extreme weather events like drought and high pest pressures. Protected varieties often require fewer inputs, are bred to resistant pests and pathogens, and can thrive in marginal conditions, contributing to more sustainable farming systems. For example, a new wheat variety called “AAC Westking” is being released into the Canadian market this year by a SeCan, a private, not-for-profit, seed grower member corporation. This new variety has yield advantages over existing varieties, while maintaining consistent performance across a wide range of environments, including dry years. Field observations from drought-stressed sites show good grain fill and large kernel size under extreme moisture stress. In this way, PVP supports both environmental stewardship and long-term food availability.

What are some of the benefits for farmers and public plant breeding institutions and the different actors in agricultural value chains?

Mr. Parker: Farmers gain access to improved varieties that enhance productivity and profitability. Public breeding institutions benefit from the ability to protect and license their innovations, generating revenue to reinvest in research. Across the value chain, PVP encourages collaboration between public and private actors, accelerating innovation through shared knowledge and joint ventures.

How can policymakers better communicate the value of PVP?

Mr. Parker: By focusing on real-world outcomes. Success stories that show how PVP leads to better yields, climate resilience, and economic growth resonate far more than abstract policy language. Clear, accessible messaging helps build understanding and public support.

Should breeders and farmers also play a role in communicating these benefits?

Mr. Parker: Absolutely. Breeders and farmers are the most credible voices when it comes to demonstrating the value of PVP. Their lived experiences and testimonials help demystify the system and show how it directly benefits agricultural communities. Peer-to-peer communication, field days, and collaborative platforms are powerful tools for outreach.

Why do you think plant variety protection is important?

Mr. Parker: Because it creates a framework where innovation is rewarded, farmers are empowered, and agriculture can evolve to meet future challenges. It’s not just about protecting intellectual property, it’s about enabling progress, access to innovation, and ensuring a productive and sustainable food system.

Any final words?

Mr. Parker: Agriculture is at the heart of human survival and prosperity. As we face climate change, population growth, and shifting global dynamics, the UPOV plant variety protection system will be key to unlocking the solutions we need. I’m proud to be part of this work and optimistic about our ability to face the challenges ahead.